Here's a quick transcription of a contemporary review of The Velvet Alley, a BBC production of Alvin Rakoff’s in which Jacqueline Hill appeared alongside Sam Wanamaker, Ted Allan and others. As far as I know, it's not preserved in any archive.

Rod Serling wrote The Velvet Alley for American television, basing it largely upon his own experiences in the industry, and the play was produced there as part of the Playhouse 90 series in January 1959. That version was recorded, and can apparently be seen on YouTube via this HuffPostTV page, though I’ve not yet tried it.

The BBC version followed on 22 November 1959. It seems to have been broadcast live; at least, so I infer from the comment about running time in the review below, which appeared without a byline in The Stage and Television Today the following week. The only photo was a little headshot of Ted Allan.

Story of the Knife-Men

Two well-known producers were sitting opposite one another discussing a certain TV contractor. Producer A was just about to join the Company. Producer B had just left the same firm.

The dialogue went something like this.

Producer A. I'm looking forward to starting

Producer B. I wouldn't if I were you. There are plenty of knife-men there.

Producer A. There are knife-men in all the ITV companies.

Producer B. That's true. You’re likely to be stabbed in the back at any of them but with this particular company it's the way they do it. I don't mind getting stabbed in the back but it's the way they hang their hat and coat on the handle that I don't like.

The interesting thing about this story is that it is perfectly true and the contractor is one of the big four. I mention it not to be cynical but to illustrate mildly how the knife-men are beginning to appear in British television.

The law of the jungle is undoubtedly here but, fortunately, not as acutely as in America.

It is against this background that American TV writer Rod Serling wrote The Velvet Alley, screened last Sunday on BBC-tv.

Machine

Serling takes as his central character a playwright, Ernie Pandish, who, after selling his first play, is turned into a machine by the ruthlessness of TV's knife-men.

He changes from a simple, ordinary man to a shouting, raving self-centred beast who succumbs to pressure from the big agency boys when they hold a carrot valued at $250,000 in front of his nose as bait.

As a result of this he discards his original agent and closest friend and forges ahead, afraid to stop, getting bigger and bigger, moving on and on into oblivion.

Nothing

Here is the PROBLEM of a man who has everything he could desire and yet has nothing. Here is a MAN who gets ten thousand dollars a script and yet has nothing to spend it on.

Serling's plot has been done many times before, but what is so interesting about this play is its characters.

I have never seen American television close at hand, and if the play is anything to go by I don't want to.

Yet the fact remains that shortly one won't have to go to America to see the people Serling has written about.

Not As Lethal

There are a few knife-men in Britain, though their daggers are not quite as lethal as those used in the States.

To start with they don't have the sponsor as their only god. Look at the producer Eddie Kirkley (played by Patrick Allen).

He comes down from the control room after seeing the show, grumbling about the last act, the writer, in fact everything.

Then he hears that the sponsor loved it. He immediately changes his attitude and puts the writer on a contract. "Call me Eddie," he says, "not Mr Kirkley."

Then there are the agents, slick and polished, hanging around like vultures awaiting the next meal. They jockey and angle to get the successful new writer on their books.

The small, honest agent – small because he is honest – like Max Sall is brushed aside. All the hard work that has gone to make the writer has gone down the drain. He doesn’t shout about what he has done.

He locks it up inside himself and bears the full burden. In doing it he gives himself coronary thrombosis.

Young

Serling allows his characters, good and bad, to flit across the screen. Some make impact, others don't.

This is the world of the young. The fittest survive and you can only survive if you can run fast enough.

You go to boring parties because you think you may meet someone there who can give you another push up the ladder to success.

But success is captured at a very high price. In this play the writer's price is his wife, his friendship for his agent and the love and respect of his father.

It was Sam Wanamaker who had the plum part of Ernie Pandish, the writer.

He appeared in nearly every scene and gave a performance rich in drama and pathos though I felt he could have been a little more subtle in certain scenes.

Best Performance

The best performance, I felt, came from Ted Allan as the pathetic agent Max Sall, who watched his friend being turned inside out, changed and mutilated and who felt every pain himself.

To a certain extent he underplayed his rôle and by doing so gave a most moving study of a man being forced to his knees by a burden he knows will ultimately crush him.

Jacqueline Hill as his wife, Pat [ED: I think Pat's actually the wife of Ernie, the main character – not, as this phrasing suggests, of Max], was also strong in a part that has been reflected by many writers both on television and films, while Annabel Maule gave an effective study of a producer’s wife worn out by parties and tired of being married to television.

The production by Alvin Rakoff was smooth with some nice angled shots and slick camera work, but it amazes me how the play could have run twenty minutes over time. I dread to think what might have happened if this had been on ITV. Sets by Barry Learoyd: Good. Lighting: Good.

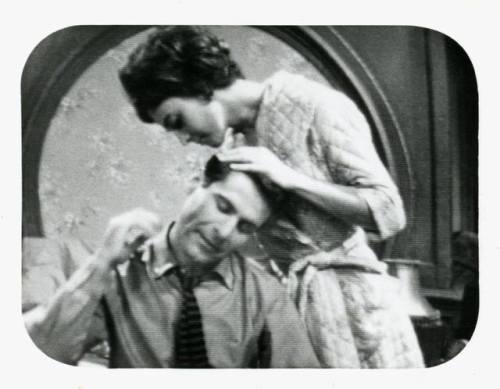

Here's a telesnap of The Velvet Alley, since Rakoff used to commission them.

Rakoff is the owner, John Cura was the author of the telesnap, and a digital version is over at Kaleidoscope.